You may have heard: there’s a new kind of memory card in town, and it’s called CFexpress.

CFexpress cards look like a pocket-drainer at first glance, starting at $199.99 / £210 for 80GB. But they’re important if you want to take advantage of the latest camera features, including 8K video capture, in-camera uncompressed video recording and ultra-rapid burst modes.

New cameras like the Sony A7S III and Canon EOS R5 have put CFexpress in the spotlight, but it’s not a brand-new format. It was announced in 2016, and the first cards came out in 2017, with the Nikon Z6 and Z7, and Canon EOS C500 Mark II video camera among the first models to have a CFexpress slot.

There’s a little more to learn about CFexpress cards, other than that they cost more than SD cards, though. Here’s everything you need to know.

Do we really need another camera memory card format?

The concept of bottlenecks explains why we need CFexpress cards. When a new camera comes along and offers fast-than-ever burst modes or higher-resolution video at greater frame rates, the processor or sensor’s raw capabilities usually get the credit.

However, the image buffer, the storage wafer in your memory card, and the storage controller all need to be up to the job too, and the CFexpress format handles the last two of these.

Its cards use PCIe 3.0, the same interface used by laptop and desktop SSDs – and these are radically faster than the SD cards most of us use today.

SD cards use a different interface. A high-spec UHS-III card has a maximum theoretical speed of around 624MB/s, while the UHS-II cards you can readily buy tap out at 312MB/s.

CFexpress raises that to 4GB/s for the fastest, Type C variant, in line with the speed of the main storage drive of a high-end laptop.

The SD Association, the organization that administers SD card standards, has come up with an alternative to CFexpress. It’s called SD Express, and uses the same PCIe 3.0 interface while offering similar max speeds of 4GB/s.

But just as SD more or less steamrolled Compact Flash for years, it seems that CFexpress has already won this fight – and its use in cameras like the Sony A7S III is proof enough.

SD Express also arrived three years after CFexpress, giving the latter a significant head start.

What kind of CFexpress cards are there?

CFexpress cards are faster – and that’s the big takeaway, if it’s all your brain has space for. But things are about to get a little more complicated.

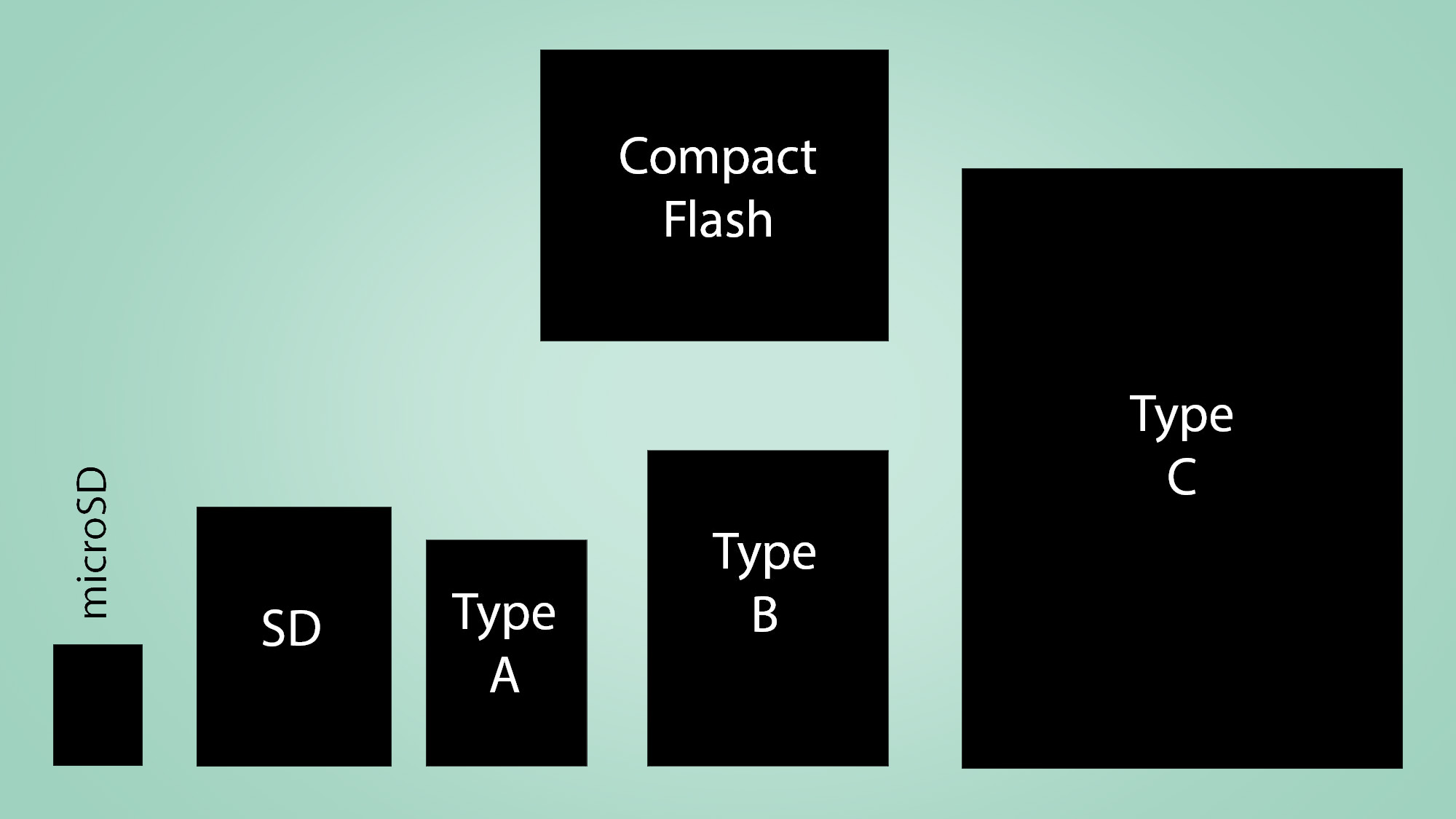

There are three CFexpress variants: Type A, Type B and Type C. The two newer ones, A and C, were introduced when the CompactFlash Association revised the standard to ‘2.0’ in 2019.

Type A has one PCIe 3.0 pipeline, for a maximum 1GB/s speed, Type B has two pipelines, doubling the headroom to 2GB/s, and Type C has four pipelines for, you guessed it, that headline-grabbing 4GB/s maximum data transfer rate.

You can currently buy Type A and Type B cards. And, like SD cards, you should also look at their sustained write speeds, rather than just those printed on the card and its packaging.

For example, the Sony Tough UHS-II series of SD cards is rated for 299MB/s write speeds, but only provides (minimum) 90MB/s sustained write speeds. Meanwhile, the Sony Tough CFexpress series, based on the Type A standard, offers burst write speeds of 700MB/s, and sustained writes at 400MB/s.

Speed losses when doing something like shooting video are much lower in a well-designed CFexpress card.

But if CFexpress Type C is faster, why wouldn’t you pick it every time?

As you can see in the diagram above, the three types of CFexpress card are not the same size. Type A cards are the smallest at 28mm x 20mm x 2.8mm, which is slightly smaller and slightly thicker than a standard SD card.

Type B cards measure 38.5 x 29.8 x 3.8mm, the same shape as XQD memory cards, while Type C cards are much larger at 54 x 74 x 4.8mm – that’s far larger and thicker than even the classic CompactFlash card of years gone by.

At present, no cameras use the CFexpress Type C standard. Several support Type B, including the Nikon Z6 and Z7. Most cameras with XQD slots can also use some Type B cards, but naturally you’ll be limited to the lower speed of that format’s interface.

The Sony Alpha A7S III (above) is the first camera to support CFexpress Type A, and this the most interesting format of the moment. Yes, it may offer the lowest performance of the lot, but these cards can fit into a combi slot that will also take SD cards.

The A7S III has two card slots, both of which will accept SD and CFexpress cards.

As for the kinds of photographers who will adopt CFexpress in the next couple of years, pros and enthusiasts with money to spend are likely to increasingly choose CFexpress, while SD will still be there for those with a lower-end camera, or those who don’t need top-tier write performance.

Who makes CFexpress cards and how much do they cost?

There’s no getting away from the fact that many photographers will find CFexpress cards prohibitively expensive.

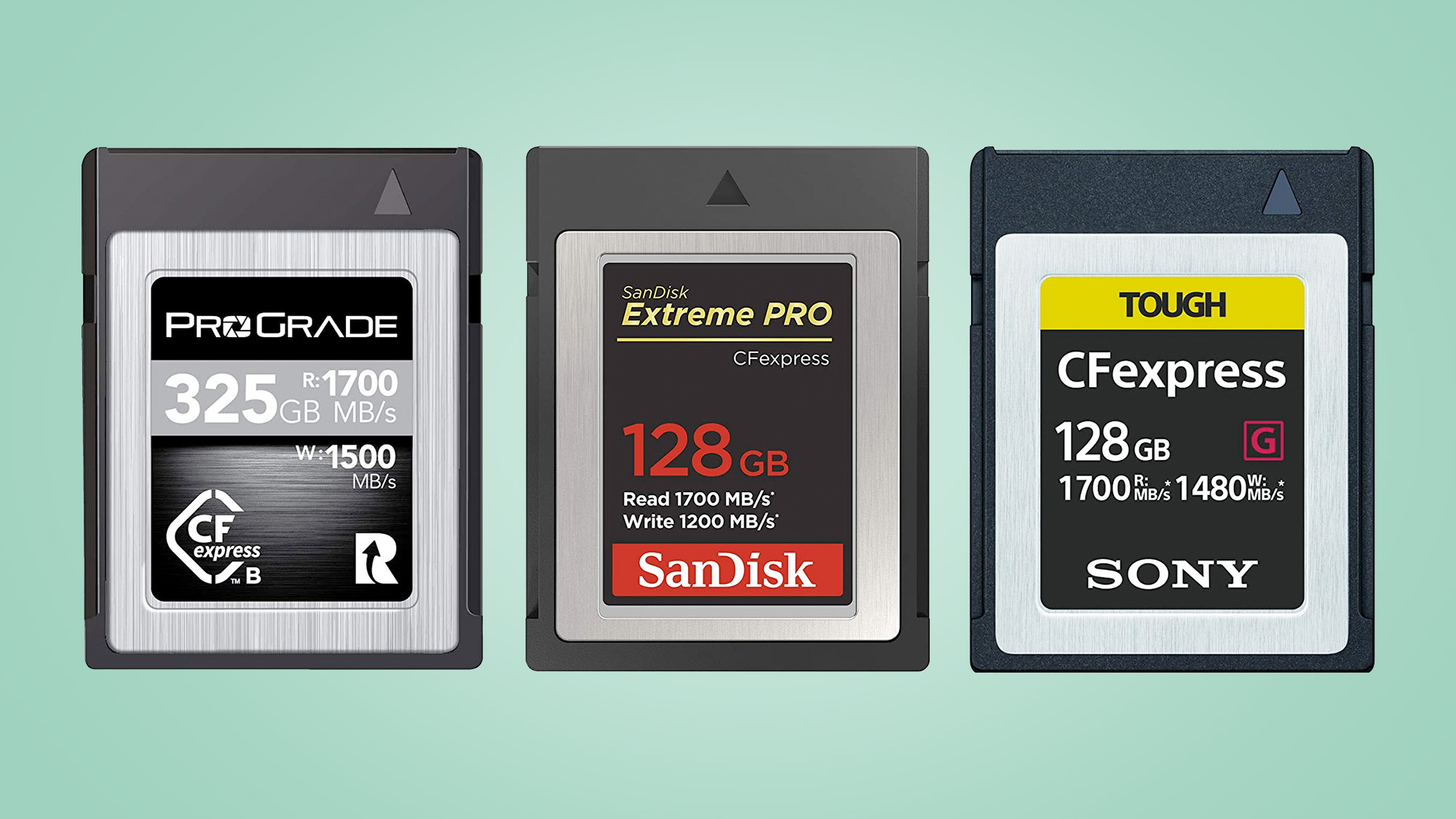

Most of the big names in SD cards are already on-board with this newer format, with Sony, Delkin, SanDisk, Lexar, ProGrade and Integral all producing CFexpress Type B cards.

There’s a significant difference in the prices of cards from these different brands. Integral and ProGrade provide the cheaper options, but may miss a feature or two; for example, ProGrade cards tend not to have an IP rating, which tells you the water and dust resistance of a product, although we have no complaints about their speed specs.

ProGrade Gold cards claim 400MB/s sustained write speeds, and its Cobalt range offers incredible sustained writes of 1400MB/s or 1500MB/s – it varies between storage levels – and you won’t find better in a Type B card, as of mid-2020.

Gold cards cost $179 / £193.99 (128GB), $399 / £279 (256GB), $399 / £499 (512GB), and $899 / £819 (1TB).

Ultra-high performance Cobalt cards are $359 / £389 (325GB) and $899 / £799 (650GB). These appear to be the fastest CFexpress Type B cards money can buy at the moment.

Integral CFexpress cards are among the cheapest around, but make no ruggedisation claims, and only appear to cite burst speed figures. However, at around £165 for the 128GB card (integral cards are much easier to find in the UK and Europe than the US), they’re pretty attractive.

Sony’s Tough CFexpress series is the top choice for travel use. They are made to three times the strength of the CFexpress standard according to Sony, and tested to withstand 70 newtons of bending force and 5-meter drops. An IP57 rating also means they’re highly water and dust resistant.

A Sony Tough card costs $219 / £299 (128GB), $399 / £483 (256GB) or $649 / £999 (512GB).

SanDisk’s highly regarded Extreme Pro series are a solid mid-price option, and will be the first choice for many. These cost $199 / £279 (128GB), $399 / £449 (256GB) or $599 / £699 (512GB), and come with a ‘lifetime’ limited warranty that covers failure, but not wear-and-tear or you accidentally snapping them.

Sony is the only company making CFexpress Type A cards at the time of writing, and these are, sadly, even more expensive than the Type B kind, at $199 / £209 for 80GB, rising to $649 for 512GB.

What’s the takeaway here? Prices vary between countries quite significantly at higher capacities, and ProGrade’s Cobalt series CFexpress cards appear to offer the best continuous write performance available in 2020.

What’s next for CFexpress?

The next stage for CFexpress is PCIe 4.0, which may come with the format’s next big revision. This would double the bandwidth per lane, so a theoretical CFexpress 3.0 card might offer 2GB/s speed for Type A sizes, 4GB/s for Type B, and 8GB/s for Type C.

We’re highly likely to see this announced at some point, because arch CFexpress-rival the SD Association has already announced PCIe 4.0 integration for a future version of SD Express cards; however, don’t expect to see these cards on sale for a couple of years at least.

There’s still a question mark over Type C cards in general, before we even think about the next CFexpress standard. You can’t buy them yet, and you have to wonder which cameras, or other devices, might take the size hit in terms of design as a trade-off in order to benefit from its 4GB/s maximum speed.

Even more intensive video capture modes are the obvious use, but do we really need 4GB/s? The efficiency of the HEVC encoding format means you won’t need anything like that data rate even at 8K 120fps.

Storage of uncompressed video is a much more obvious use case for all that bandwidth. This is normally done over HDMI, as a 2.1-version connector has 48Gbps bandwidth (6GB/s). So while a CFexpress Type C card isn’t quite as fat a pipe as HDMI, it comes much closer than the cards we have today, and would let you store incredibly high data-rate footage in-camera.

What we’re really waiting for is something much simpler: lower prices.

We hope the cost of 64-256GB CFexpress cards will start to drop as manufacturing scales up, but don’t expect miracles – a 256GB UHS-II SD card with a V90 rating (continuous 90MB/s write speed) can still cost around $250, so there’s less pressure for CFexpress prices to freefall in the next 12 months.

from TechRadar - All the latest technology news https://ift.tt/2Ph3ApA